By Victoria Plum

Having enjoyed Hawk Honey’s enthusiastic discourse on “Wasps, Malicious or Misunderstood?” at last week’s meeting of the Reepham & District Gardening Club (I think we know the answer to this question), I lay in bed carefully composing my report on this fascinating talk and regretting that I have very few wasp photos to show you in my collection.

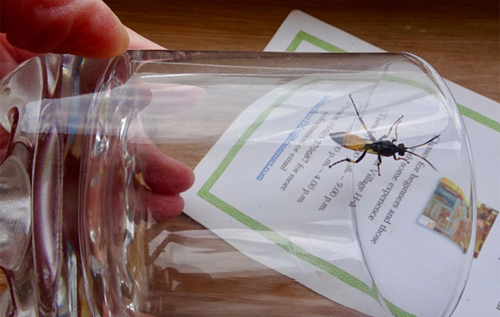

Then off for my shower, when I saw a movement at the window and managed to catch this wasp (above), using my favoured technique of placing a glass over the insect and then sliding a card under to imprison the creature for inspection and then safe release.

If only this had happened the day before, I could have asked the expert for identification.

There are about 9,000 species of wasp, including 610 species of solitary wasp and endless parasitic wasps, but which is this (below)? (I’ve now had another look and am pretty sure it’s an Ichneumon stramentor.)

Those we know are the nine sorts of social wasps, living in beautifully built colonies.

We think of them as “picnic spoilers”; we expect them in late summer but at that time their only concern is to find a “sugar rush”, hence their interest in your can of lager or the fallen fruit under your tree as they come to the end of their life.

They don’t get up in the morning to go out looking for humans to sting!

But most wasps look very different: tiny waisted, short, fat, long, thin or very tiny as we saw from Mr Honey’s photos.

We saw leafhoppers (they make cuckoo spit) shield bugs, aphids and caterpillars being parasitised, that is having an egg laid inside the anaesthetised body to provide sustenance for the hatchling.

We saw wasps excavating, building and nesting, all observed and filmed by our speaker.

If you put a tree log with a variety of holes drilled in it in full sun, upright (so as not to be damp), wasps will come (other insects too) and you too can watch them up close.

The message is that every single one of these creatures has a job to do and a place to fill in nature: each one depends on another and is depended upon in turn.

So, use chemicals in your garden at your peril – and that means everyone else’s peril.

Photos: Tina Sutton